A short story

“The company, halt the march! We’ll spend the night here!” I commanded.

The few remaining log buildings from the former village Zorka stood empty and abandoned. But for the soldiers, tired from the long trek, rest and sleep under the roofs of dilapidated barns was a gift of fate. The next day we were preparing to reach the front line and join the battle. The company was supposed to replenish the regular army, but for now it mainly consisted of fighters from sabotage and partisan detachments walking through the Smolensk forests. Having folded their white camouflage coats and skis in the corner of the barn, the soldiers enjoyed a hot dinner and tea from the field kitchen. This came great before bed.

“Comrade senior lieutenant, won’t you give us some vodka?”

“Not now, but if an order for a battle comes, you’ll receive it.”

“Yes, at first they will save vodka, but then, you see, not everyone will need it,” said the middle-aged soldier.

“Don’t funk, Terentich. You had enough vodka for your lifetime!” his friends laughed merrily.

“This is just to relieve tension guys! Look, what the poet thinks: there’s nothing worse than waiting for an attack. Sarik, Sarik, read some your poetry,” the machine gunner addressed his partner.

A handsome black-haired guy with almost fused eyebrows did not make any excuses. He took a dirty notebook out of his duffel bag and, without looking at it, quickly and slightly intoned began to read poetry:

“They sing when going for the death,

Although before they cried by pack.

Because most dreadful time of stress –

The hour of waiting for attack.”

He was reading, and the soldiers became silent. It was about them. About their fate. About the soldier’s doom. About life and death, which takes some and, turning away indifferently, passes by others. And your heart skips a beat, waiting, when is it your turn?

“But we can’t wait it anymore,

Through trenches led by frozen hate

We’re piercing necks with rage and gore

And bayonet is our mate.

And someone will be lucky enough to survive this fight, and then another one, and then…?

“The fight was brief. And after day

We icy vodka swigged a lot,

And with a knife I scraped away

From under nails the foreign blood.”

I lay down at the corner for a while. I knew this young poet, a neighbor in our yard. Only their windows, in Gudzenko’s apartment, overlooked Tarasovskaya Street, and ours, of the Vigdors’ apartment, overlooked Leo Tolstoy Street. This was when we lived in Kiev, and my father was developing rocket shells. Even before his group was transferred to Kharkov to equip combat vehicles and tanks.

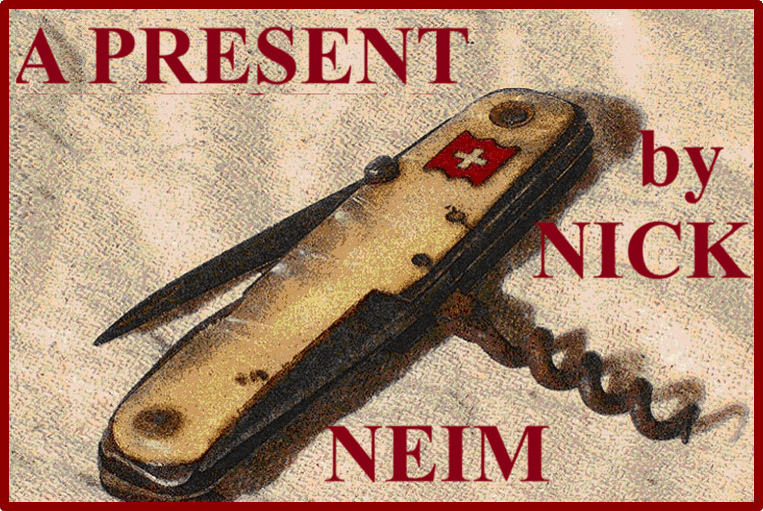

There, in Kharkov, in 1938 he was arrested, but before the arrest he managed to give me his talisman, his favorite pocket knife with a small white cross on a red shield. A knife that had an unusual history…

*

The summer of 1916 in Zurich was unusually pleasant. The third year was behind him, and Boris Vigdor was on his way to the coveted degree of Doctor of Engineering. In a way, he was lucky. In Russia, with its medieval laws, he could not even think about a prestigious university and, if he had stayed in the country, he would now be fighting somewhere in Galicia, in the army of General Brusilov. If he had chosen France or Germany to study, he could have sat in the trenches near Verdun. The war had been raging in Europe for two years now, and Switzerland remained a small island of peace in which studies continued as usual.

Now, during the holidays, Boris’s main concern was to earn money to pay for the next semester, and he did not disdain any part-time job to supplement his small salary in the mechanical workshop of his favorite institute. Although Polytechnic Institute had already changed its name to Federal Technological Institute five years ago, students still affectionately called it “Poly.” And “Poly” reciprocated them: he taught, gave work and his audience for student meetings. True, in the summer the Russian circle gathered at the cafe “Jacqueline” on the shore of the city lake. Here, on weekends, they spent hours arguing about war and revolution, admiring the view of the Alps, riding boats and dreaming about the future.

A week ago, a man of about thirty, with unruly hair of dark hair, dressed in a good English suit, with an accent from the Baltics or Great Britain, appeared in their company. He was brought by Stepan Stepanov, a University student. Stepanov recited poems by Nadson and Blok, and his companion listened with visible pleasure. On the terrace, Stepan introduced the guest to Boris,

“This is my patron from England, Mr. Jacob. I praised very much our circle members to him, so he decided to meet them on occasion.”

“Jacob,” the patron nodded. “Well, that is, Yakov,” the handshake was strong. “And, come on, let’s communicate without ceremonies, because we are both Russians. I was told that you, Mr. Vigdor, are well versed in mechanics. Is it true?”

“Halfway there,” Boris answered. “But I can fix a lot of mechanical things. Is this what you meant? What is the task?”

Yakov glanced around and continued,

“There is an order. Pistols repair. I anticipate your questions. The weapon is illegal, but “clean”, not involved in crime. This is a factory defect. We need to help to our own people. Stepan told me about your views. They largely coincide with my point of view and with the views of my Swiss friends. And also… you will be paid well. By money transfer – directly to your bank account.”

Boris did not hesitate for long. Everything was clear: Yakov was not some student member of a circle, but a real revolutionary, from among the many who flooded Switzerland. The game was worth the candles: they paid generously, and weapons were Vigdor’s strong point. As for secrecy – he himself locked the workshops in the evening after cleaning.

So, his part-time work began without delay. The money was carefully transferred from an unknown donor. One day, handing over another well-functioning revolver to Stepan, Boris asked,

“Who is transferring the money, Mr. Jacob or Mr. X”?

“Mr. Ex,” Stepanov smiled, and Vigdor did not understand whether this was an allusion to England or to the already rare acts of expropriation of the Socialist Revolutionaries and Bolsheviks.

Since September, Boris has had much less time, but orders have been coming in less and less. The news from everywhere was alarming. At Verdun, no one achieved anything, but only killed one and a half million soldiers. The Lutsk breakthrough in Galicia ended unsuccessfully. And unexpectedly for everyone, a revolution occurred in Russia. At a meeting of the circle members, Stepan whispered to Boris,

“There will be no more orders. I’m leaving.”

“What, are you going to Russia? Now? What about classes?”

“Now we are needed there more. Will you return to Russia?”

“Of course, Styopa! To a new, democratic Russia! As an engineer who can freely live and work anywhere in the country.”

“Do it! The country will need your knowledge. Yes, by the way, your customer sent you a souvenir from him. For memory and for good luck, like a talisman. See, it has also a cross on it,”

and he handed Boris a brand new shiny steel pocket knife with an emblem – a white cross on a red shield – the trademark of a company of knives for the Swiss National Guard.

The thick body of a pocket knife, hiding many blades, saws, screwdrivers and other tools, useful in skillful hands, lay into Boris’s palm with its pleasant heaviness.

“They say these military knives save the lives of their owners. After all the Swiss don’t fight.”

“Give my gratitude to the customer. I don’t know what to call him.”

“His last name won’t tell you anything,” Stepan smiled. “A simple Russian surname – Lenin.”

*

At five AM we were already up. We washed ourselves with snow, relieved ourselves and went ahead to the position. Those who saved the bread crusts from the evening chewed on them. Many simply drank cold tea and smoked. Soldiers got ready quickly. The march-push to the front line was a short one.

“Here you have motorized infantry,” thought Senior Lieutenant Vladimir Vigdor, “no cars, no motorcycles. One truck for camp kitchen, onto which a mortar was also loaded, to the obvious displeasure of the cook.

Who could have expected that motorized infantry, in gray enemy overcoats, would appear from behind the forest? The soldiers did not have time to fall into the snow when they were doused with clods of earth from the first shot of a light cannon. Someone was wounded, someone was screaming and swearing, Semyon was setting up his heavy machine gun, light hand machine guns were firing, a mortar banged and several grenades exploded. The Germans ran towards them, trying to sweep away the enemy in hand-to-hand combat.

“Go ahead, guys!” the company commander shouted, and at that moment it was as if a hammer had hit him in the chest, in the heart, and darkness fell…

*

The evacuation hospital in Kostroma was working at full capacity. Seriously wounded people who underwent surgery in front-line hospitals were admitted here.

“Anya! Run quickly to the ward six! Gudzenko is bleeding again!”

The nurse threw her pen on the open magazine and, grabbing a dressing bag, rushed down the corridor,

“I’ll go to the ward, and you, Polina, ask the surgeons, maybe they should take the patient to the OR?” she said to the nurse aid on the way. “Have you fed him yet? Wait with the food!”

His bedmate in the ward was nervous,

“Faster, Anya, faster. Cut the bandages? Here, my knife, it’s very sharp.”

“Don’t worry Vigdor, and don’t get up! With a lung contusion you have to lie down. And we will help your friend. Everything will be OK.”

They were brought in to the hospital together, wounded in a heavy battle, in which more than half of the fighters died. “And with many who are lucky to be alive will still have to tinker,” Anya thought, removing the wet bandages and pressing on the wound, while waiting for the surgeon. Both patients have already been operated on once. Gudzenko got the bullet in the stomach.

“Like Pushkin,” he joked.

And Vigdor was a lucky guy. The bullet hit him directly in the pocketknife hidden in his tunic pocket and bounced off. The knife, however, broke a rib from the blow and contused a lung, but if it had not been in the pocket, one more man would have died in the company.

*

The NKVD officer with rhombi in his buttonholes seemed familiar to Boris.

“Where, where?” he thought intensely. His fate could depend on the solution to this problem. Or maybe it couldn’t.

“The officer read my file, he knows me much better than I know him. If he wants to, he will open up; if he doesn’t want to, he will complete the task without it.”

The head of the missile group, Doctor of Science Boris Vigdor, had no doubt that this task was to destroy the leading scientists and designers of the young republic. He even suspected that high officials from the OGPU were involved in this. He recognized one of them – the Zurich visitor Jacob. But he was already brought to the land of shadows by his own merciless friends in persecuting ghostly enemies. But if Yakov changed only slightly, this investigator should be recognized in a different body: slender, young, without a mustache…

“Stepan?” Vigdor said, barely moving his lips, “You? Jacob’s friend?”

The security officer winced and rubbed the tip of his nose with his index finger, at the same time sawing across his lips, as if depicting a sign “Hush, be silent!”

“Citizen Vigdor, the commission for combating enemies in science recognized the actions of your group as criminal. The leaders will suffer the punishment they deserve. The matter was endorsed at the highest level.”

He opened the folder to some page, and Boris saw the familiar blue pencil stroke: “I. St…”

“Nevertheless,” Stepanov continued, “the deadline is not defined, and this gives you a significant chance to live until better times. You will be sent to labor camps, and I, in memory of working for one customer, will try to find a better use for your knowledge than logging.”

Vigdor really wanted to ask Stepanov about the events of distant 1916, about the mysterious customer Lenin, whose name is now familiar to all people on Earth. But Stepan continued to signal to him, and intuition told Boris that he should remain silent in order to give Lenin’s present an opportunity to exercise its saving talisman properties.

*

They were sitting on a bench in the garden around the hospital. Two peers, guys from the same yard, defenders of the Motherland. People of similar appearance and fate.

“We won’t die of old age, we’ll die of old wounds,” said Semyon, lighting a cigarette and taking out his crumpled notebook, where he wrote down his poems. “But you might be lucky with your family amulet named after Lenin. So you will see a bright future when we defeat fascists of all kinds.”

“Vigdor, there is a letter for you! By a man’s hand, from your father, probably!” shouted the nurse aid Polina, waving with a white paper triangle.

Damn it! She turned out to be right. Several lines were written in my father’s calligraphic handwriting,

“Fight boldly, my dear defender. A knife can really save you! I’ll tell you the whole story when we meet. Keep it safe. I also want to see my grandson whittling a model of a space rocket with it.

P.S. I have a wonderful boss, his name is Sergei Pavlovich.

I hug you tightly.

Your father, B.V.”